There are books and there are books, aren’t there?

I was prepared to like this. A feminist unpacking of one of literature’s greatest forgotten women? It sounded right up my alley, even as an avid fan of Orwell, who I knew (you just know, don’t you?) wasn’t going to fare well in this biography.

So. I knew I’d like it. I wasn’t prepared to cry reading it (twice!), or to want to rave about it to every person I passed in the street. “Have you ever read Animal Farm?” I wanted to ask. “Did you know it wouldn’t have existed if not for Eileen Orwell, a woman Orwell never so much as references in the dedication?”

And “What about Homage to Catalonia? Did you know Orwell refers to his wife thirty-seven times, but never once by name? Did you know while he was off in Alcubierre firing no more than three bullets in three weeks, she was in the thick of it all in Barcelona, dodging spies and handling operations?”

I raved and ranted to my husband. In the fashion of someone who wasn’t reading, nor was very interested in reading, the book I was engrossed with, he said “Oh, geez,” about a particularly horrible detail of Eileen’s life, then turned back to his video game.

Meanwhile, I have dreamed about Eileen for a week.

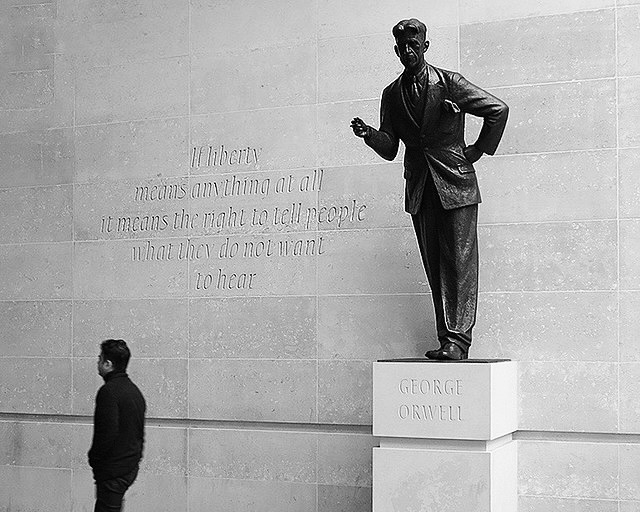

Anna Funder’s aim was to unearth her. Specifically, to unearth her from the burial ground Orwell had put her in; to uncover a truth hidden in the messy. sordid reality of George Orwell’s life, as Orwell himself had once done to Salvador Dali, a man he was disgusted by.

“A biography,” wrote Orwell through his disgust, “is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.”

Make no mistake, Wifedom unearths Eileen Blair, and reveals something disgraceful as it does. It reveals the patriarchy that stoppered Eileen Orwell’s promising career. It reveals her squandered brilliance; squandered and forgotten–consciously or unconsciously–by her husband. And it reveals his disgraceful neglect of her; something that, at the very least, let her careless doctors get away with botching her hysterectomy. At the very worst, it killed her.

It can be difficult to hold up the usual literary heroes as a woman. Nevertheless, I am a big fan of Orwell. Like many others, I read both Animal Farm and 1984 in high school. In 2012, I read Down and Out in Paris and London in Edinburgh, during the Fringe Festival. I went to Barcelona in 2015 and read Homage to Catalonia while I was travelling. I have always admired Orwell for his ability to skewer any political system he came across, and I admired his courage in committing to the craft of writing, no matter his financial circumstances. Little did I know, he could remain a writer because of the generosity of women in his life—his aunt, his sisters, and most notably, his first wife. Eileen.

It is understandably tricky to find evidence of these women, but it is there in passings mention of her, both in Orwell’s work and his biographers’. It is in the passive voice. Funder does a particularly good job in translating both Orwell’s use of the passive voice to erase his wife, and his biographers’ attempts to do the same. Things are “organised for” Orwell. They are “arranged for” him. Who organises? Who arranges? The women unseen. Often, Eileen.

Orwell’s lack of thanks to these women is a particularly egregious thing to consider in a book written by a working writer — Anna Funder — who is working through a realisation that she does the lion’s share of her household’s domestic and emotional labour. Funder’s own consideration of her life is no small part of this book. She is angry, as many women are, when she examines her own circumstances. Somewhow, despite being no less successful than her husband, and having promised herself never to be the woman who ends up doing everything, she has become a victim of Wifedom; handling everything, everywhere all at once, with no thanks and no easy path to equilibrium. Even her daughter notices it. The parallel of her own life with Eileen’s sometimes reads as projection, but only very rarely, and only in small, fictionalised segments of this book that the reader is trained to take with a grain of salt.

And then, onto darker things. Orwell had a well-documented penchant for “surprising” and “jumping on” women, especially in parks. There is the story of his young, unrequited love of a woman who refuses to sleep with him: he tries to force her down on a walk in the park to rape her. There is the story of Lydia, a friend of Eileen’s whose dislike of George Orwell was so obvious it repelled even Eileen from friendship with her. Upon visiting George in hospital in Eileen’s place–Eileen is ill and unable to visit–Lydia finds herself pounced upon by Orwell, putting in the impossible position of speaking out and potentially losing a friend, or keeping quiet and letting the violation eat at her. There are young prostitutes in Burma and Morocco (the latter of which he holds over his wife’s head), and the whispers of sadism that follow him around. There are the indiscreet affairs with secretaries at the Tribune and the BBC; secretaries his wife has to deliver transcripts to with a smile. Orwell’s use and abuse, and frank dislike of women seems so egregious that it might be made up. It is not. Funder is quoting from very reliable sources. Even Orwell’s most sycophantic biographers cannot deny what is happening.

None of this is to mention the homophobia, which is disturbingly rampant even for the era. Plenty of Orwell’s friends and acquaintances make that point, since there was a openly secret culture, especially in boarding school and in the military, of boys and men getting off with each other that Orwell railed against so much that it drew attention. The man doth protest too much, etc. Funder does an exceptional job of handling the question of Orwell’s rumoured homosexuality. The answer, vague though it must be, seems to be yes, there was every chance Orwell was homosexual, and he was so disgusted by it that he repressed it until his desire looked nothing like desire; instead, it looked like sadism and hate.

Among men, notes Funder, is where Orwell most wants to be, for more reasons than he can admit to himself. Obviously, there are still questions up in the air, and there is no direct evidence to quote, but this is a book written by looking in between the lines, and there are certainly signs there in the words that aren’t said.

Above all that–the rape and the rampant homophobia–the part of this book that makes me weep a line in a letter written from Eileen to Orwell. This incredible woman, who was enrolled at UCL, studying a Masters in psychology when she met Orwell, who edited and typed his work, who originated the fable of Animal Farm, whose diary Orwell used to name 1984, who was the breadwinner for many years of their marriage…this woman writes to her husband about an upcoming hysterectomy, trying to justify the cost of it of doing it on the cheap (though they could still realistically have afforded it otherwise), and concludes, horrifyingly:

I really don’t think I’m worth the money.

I read that line knowing I was reading the words of a woman broken down by an emotionally abusive husband.

Orwell did not accompany her to the surgery. Nor was he there for the months of pain that preceded it. Instead, he jaunted off, unannounced, to Europe, where he wrote largely unimportant stories as a foreign correspondent for the Tribune. Funder, as well as many of Orwell’s friends called that what it was: abandonment.

In the end, I am left with this:

When people–especially men–talk about the concept of doublethink as outlined in 1984, they herald it as a product of clever political insight. And in many ways, it is. Orwell lived a life surrounded by doublethink: first, in Burma, in a colony held up by racist structures, and then in Spain, where the Monty Python-eque alphabet soup of Spain’s communist parties turned on each other instead of Franco’s fascists. But it’s clear Orwell himself was not above doublethink. He came from a family of strong, opinionated, intellectually-minded women, many of whom he owed his success to. He also used these women and assumed they ought to work for him, rather than themselves. He approved of Eileen’s decision to remove ‘obey’ from her wedding vows, but in all other aspects was a misogynist. What is patriarchy, notes Funder, but doublethink? Orwell could write about it because he knew it well, not just from observation.

At the end of reading Wifedom, I knew precisely where the worst, most terrible and misogynistic parts of 1984′s Winston originated. I knew where Orwell found the part of Winston that begged for his lover to be thrown to the rats. It was in himself. In the man who, in his own (rather understated) words, treated his wife badly.

I don’t think it would be a stretch to say this is why, in life, Orwell forbid anyone to write a biography of him. Perhaps, like many of us who turn away from the worst parts of ourselves, he was afraid of seeing the evidence of his own disgraceful actions.

Rating: 5/5. 100/5. A must read.

This post was previously published on my old blog, Mac at the Library.

Leave a comment